ภาษาสันสกฤต

ภาษาสันสกฤต (มาจากคำว่า संस्कृत-, สํสฺกฺฤต-,[9][10] แปลงเป็นคำนาม: संस्कृतम्, สํสฺกฺฤตมฺ)[11][b] เป็นภาษาคลาสสิกในเอเชียใต้ที่อยู่ในสาขาอินโด-อารยันของตระกูลภาษาอินโด-ยูโรเปียน[12][13][14] ภาษานี้เกิดขึ้นในเอเชียใต้หลังจากที่ภาษารุ่นก่อนหน้าได้แพร่กระจายไปที่นั่นจากทางตะวันตกเฉียงเหนือในยุคสัมฤทธิ์ตอนปลาย[15][16] ภาษาสันสกฤตเป็นภาษาศักดิ์สิทธิ์ในศาสนาฮินดู ภาษาของปรัชญาฮินดูคลาสสิก และภาษาของวรรณกรรมศาสนาพุทธและศาสนาเชนในอดีต นอกจากนี้ยังเป็นภาษากลางภาษาหนึ่งในเอเชียใต้สมัยโบราณถึงสมัยกลาง และในช่วงการเผยแผ่วัฒนธรรมฮินดูกับพุทธไปยังเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ เอเชียตะวันออก และเอเชียกลางในสมัยกลางตอนต้น ได้กลายเป็นภาษาทางศาสนาและวัฒนธรรมชั้นสูง และภาษาของผู้ทรงอำนาจทางการเมืองในบางภูมิภาค[17][18] ด้วยเหตุนี้ ภาษาสันสกฤตจึงมีอิทธิพลอย่างยาวนานต่อภาษาในเอเชียใต้ เอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ และเอเชียตะวันออก โดยเฉพาะอย่างยิ่งในวงศัพท์ทางการและวงศัพท์วิชาการของภาษาเหล่านั้น[19]

| ภาษาสันสกฤต | |

|---|---|

| संस्कृतम् สํสฺกฺฤตมฺ | |

| [[File:

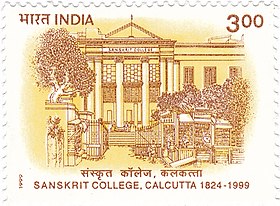

(บน) เอกสารตัวเขียนภาษาสันสกฤตสมัยคริสต์ศตวรรษที่ 19 จาก ภควัทคีตา[1] ซึ่งแต่งขึ้นในช่วงประมาณ 400–200 ปีก่อนคริสต์ศักราช[2][3] (ล่าง) แสตมป์ครบรอบ 175 ปีของวิทยาลัยสันสกฤตโกลกาตา วิทยาลัยภาษาสันสกฤตที่เก่าแก่เป็นอันดับที่ 3 (ส่วนอันดับที่ 1 คือวิทยาลัยสันสกฤตพาราณาสีซึ่งก่อตั้งใน ค.ศ. 1791) |200px]] | |

| ออกเสียง | [sɐ̃skr̩tɐm] |

| ภูมิภาค | เอเชียใต้ (สมัยโบราณถึงสมัยกลาง), บางส่วนของเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ (สมัยกลาง) |

| ยุค | ประมาณ 1,500–600 ปีก่อนคริสต์ศักราช (ภาษาพระเวท);[4] 700 ปีก่อนคริสต์ศักราช – ค.ศ. 1350 (สันสกฤตแบบแผน)[5] |

| ตระกูลภาษา | อินโด-ยูโรเปียน

|

| รูปแบบก่อนหน้า | ภาษาพระเวท

|

| ระบบการเขียน | แต่เดิมเป็นภาษาที่สืบมาโดยมุขปาฐะ ไม่พบหลักฐานตัวเขียนจนกระทั่งศตวรรษที่ 1 ก่อนคริสต์ศักราช เมื่อมีการเขียนเป็นอักษรพราหมี และต่อมาเขียนเป็นอักษรต่าง ๆ ในตระกูลพราหมี[a][6][7] |

| สถานภาพทางการ | |

| ภาษาทางการ | |

| ภาษาชนกลุ่มน้อยที่รับรองใน | |

| รหัสภาษา | |

| ISO 639-1 | sa |

| ISO 639-2 | san |

| ISO 639-3 | san |

โดยทั่วไป สันสกฤต สื่อความหมายถึงวิธภาษาอินโด-อารยันเก่าหลายวิธภาษา[20][21] วิธภาษาที่เก่าแก่ที่สุดในกลุ่มนี้คือภาษาพระเวทในคัมภีร์ ฤคเวท ซึ่งประกอบด้วยบทสวด 1,028 บทที่แต่งขึ้นในช่วงระหว่าง 1,500 ถึง 1,200 ปีก่อนคริสต์ศักราชโดยชนเผ่าอินโด-อารยันที่ย้ายถิ่นจากบริเวณที่เป็นอัฟกานิสถานในปัจจุบันไปทางตะวันออก ผ่านตอนเหนือของปากีสถาน แล้วเข้าสู่ตอนเหนือของอินเดีย[22][23] ภาษาพระเวทมีปฏิสัมพันธ์กับภาษาโบราณที่ปรากฏอยู่ก่อนแล้วในอนุทวีป โดยรับชื่อเรียกพืชและสัตว์ที่ค้นพบใหม่เข้ามาใช้ในภาษา นอกจากนี้ ภาษากลุ่มดราวิเดียนโบราณยังมีอิทธิพลต่อระบบสัทวิทยาและวากยสัมพันธ์ภาษาสันสกฤตด้วย[24] สันสกฤต ในนิยามอย่างแคบอาจหมายถึงภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน ซึ่งเป็นรูปแบบไวยากรณ์ที่ผ่านการขัดเกลาและปรับเป็นมาตรฐานในช่วงกลางสหัสวรรษที่ 1 ก่อนคริสต์ศักราช และได้รับการจัดประมวลใน อัษฏาธยายี ตำราไวยากรณ์โบราณที่มีความครอบคลุมมากที่สุด[25] กาลิทาส นักเขียนบทละครผู้ยิ่งใหญ่ แต่งผลงานเป็นภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน และรากฐานของเลขคณิตสมัยใหม่ได้รับการอธิบายครั้งแรกเป็นภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน[c][26] อย่างไรก็ตาม มหากาพย์ภาษาสันสกฤตที่สำคัญอย่าง มหาภารตะ และ รามายณะ นั้นได้รับการแต่งขึ้นโดยใช้ทำเนียบภาษามุขปาฐะที่เรียกว่าภาษาสันสกฤตมหากาพย์ ซึ่งใช้กันในตอนเหนือของอินเดียระหว่าง 400 ปีก่อนคริสต์ศักราชถึง ค.ศ. 300 และร่วมสมัยกับภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน[27] ในหลายศตวรรษถัดมา ภาษาสันสกฤตได้กลายเป็นภาษาที่ผูกติดกับประเพณี ไม่ได้รับการเรียนรู้เป็นภาษาแม่ และหยุดพัฒนาในฐานะภาษาที่ยังมีชีวิตไปในที่สุด[28] ทั้งนี้ ไม่พบหลักฐานว่าภาษาสันสกฤตมีตัวอักษรเป็นของตนเอง โดยตั้งแต่ช่วงเปลี่ยนคริสต์สหัสวรรษที่ 1 มีการเขียนภาษานี้โดยใช้อักษรต่าง ๆ ในตระกูลพราหมี และในสมัยใหม่ ส่วนใหญ่เขียนโดยใช้อักษรเทวนาครี[a][6][7]

สถานะ หน้าที่ และตำแหน่งของภาษาสันสกฤตในมรดกวัฒนธรรมของอินเดียได้รับการรับรองผ่านการระบุรวมอยู่ในกำหนดรายการที่แปดของรัฐธรรมนูญอินเดีย[29][30] อย่างไรก็ตาม ถึงแม้จะมีความพยายามฟื้นฟูภาษานี้[31][32] ก็ยังไม่มีผู้พูดภาษาสันสกฤตเป็นภาษาแม่ในอินเดียเลย[33][32][34][35]

ประวัติ

แก้ในภาษาสันสกฤต คำคุณศัพท์ สํสฺกฺฤต- (संस्कृत-) เป็นคำประสมที่ประกอบด้วย สํ ('พร้อม, ดี, สมบูรณ์แล้ว') และ สฺกฺฤต- ('ทำแล้ว, สร้างแล้ว, งาน')[36][37] หมายถึงงานที่ "เตรียมไว้อย่างดี, บริสุทธิ์และสมบูรณ์, ขัดเกลา, ศักดิ์สิทธิ์"[38][39][40] ตามไบเดอร์แมน (Biderman) ซึ่งเป็นภาษาของชนชั้นพราหมณ์ ตรงข้ามกับภาษาพูดของชาวบ้านทั่วไปที่เรียกว่าปรากฤต ภาษาสันสกฤตมีพัฒนาการในหลายยุคสมัย โดยมีหลักฐานเก่าแก่ที่สุด คือภาษาที่ปรากฏในคัมภีร์ฤคเวท (เมื่อราว 1,200 ปีก่อนคริสตกาล) อันเป็นบทสวดสรรเสริญพระเจ้าในลัทธิพราหมณ์ในยุคต้น ๆ อย่างไรก็ตาม ในการจำแนกภาษาสันสกฤตโดยละเอียด นักวิชาการอาจถือว่าภาษาในคัมภีร์ฤคเวทเป็นภาษาหนึ่งที่ต่างจากภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน (Classical language) และเรียกว่า ภาษาพระเวท (Vedic language) ภาษาพระเวทดั้งเดิมยังมิได้มีการวางกฎเกณฑ์ให้เป็นระเบียบรัดกุมและสละสลวย และมีหลักทางไวยากรณ์อย่างกว้าง ๆ ปรากฏอยู่ในบทสวดในคัมภีร์พระเวทของศาสนาฮินดู เนื้อหาคือบทสวดสรรเสริญเทพเจ้า เอกลักษณ์ที่ปรากฏอยู่เฉพาะในภาษาพระเวทคือระดับเสียง (accent) ซึ่งกำหนดไว้อย่างเคร่งครัด และถือเป็นสิ่งสำคัญของการสวดพระเวทเพื่อให้สัมฤทธิผล

ภาษาสันสกฤตมีวิวัฒนาการมาจากภาษาชนเผ่าอารยัน หรืออินโดยูโรเปียน (Indo-European) บรรพบุรุษของพวกอินโด-อารยัน ตั้งรกรากอยู่เหนือเอเซียตะวันออก (ตอนกลางของทวีปเอเชีย - Central Asia) โดยไม่มีที่อยู่เป็นหลักแหล่ง กลุ่มอารยันต้องเร่ร่อนทำมาหากินเหมือนกันชนเผ่าอื่น ๆ ในจุดนี้เองที่ทำให้เกิดการแยกย้ายถิ่นฐาน การเกิดประเพณี และภาษาที่แตกต่างกันออกไป ชนเผ่าอารยันได้แยกตัวกันออกไปเป็น 3 กลุ่มใหญ่ กลุ่มที่ 1 แยกไปทางตะวันตกเข้าสู่ทวีปยุโรป กลุ่มที่ 2 ลงมาทางตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ อนุมานได้ว่าน่าจะเป็นชนชาติอิหร่านในเปอร์เซีย และกลุ่มที่ 3 เป็นกลุ่มที่สำคัญที่สุด กลุ่มนี้แยกลงมาทางใต้ตามลุ่มแม่น้ำสินธุ (Indus) ชาวอารยันกลุ่มนี้เมื่อรุกเข้าในแถบลุ่มแม่น้ำสินธุแล้ว ก็ได้ไปพบกับชนพื้นเมืองที่เรียกว่า ดราวิเดียน (Dravidian) และเกิดการผสมผสานทางวัฒนธรรมและภาษา โดยชนเผ่าอารยันได้นำภาษาพระเวทยุคโบราณเข้าสู่อินเดียพร้อม ๆ กับความเชื่อทางศาสนา ซึ่งในยุคต่อมาได้เกิดตำราไวยากรณ์ภาษาสันสกฤตคือ อษฺฏาธฺยายี (अष्टाध्यायी "ไวยากรณ์ 8 บท") ของปาณินิ เชื่อกันว่ารจนาขึ้นในช่วงพุทธกาล ปาณินิเห็นว่าภาษาสันสกฤตแบบพระเวทนั้นมีภาษาถิ่นปนเข้ามามากพอสมควรแล้ว หากไม่เขียนไวยากรณ์ที่เป็นระเบียบแบบแผนไว้ ภาษาสันสกฤตแบบพระเวทที่เคยใช้มาตั้งแต่ยุคพระเวทจะคละกับภาษาท้องถิ่นต่าง ๆ ทำให้การประกอบพิธีกรรมไม่มีความศักดิ์สิทธิ์ ดังนั้น จึงแต่งอัษฏาธยายีขึ้น ความจริงตำราแบบแผนไวยากรณ์ก่อนหน้าปาณินิได้มีอยู่ก่อนแล้ว แต่เมื่อเกิดอัษฏาธยายีตำราเหล่านั้นก็ได้หมดความนิยมลงและสูญไปในที่สุด ผลของไวยากรณ์ปาณินิก็คือภาษาเกิดการจำกัดกรอบมากเกินไป ทำให้ภาษาไม่พัฒนา ในที่สุด ภาษาสันสกฤตแบบปาณินิ หรือภาษาสันสกฤตแบบฉบับ จึงกลายเป็นภาษาเขียนในวรรณกรรม ซึ่งผู้ที่สามารถจะอ่าน เขียนและแปลได้จะต้องใช้เวลามากพอสมควร

ภาษาสันสกฤตแบ่งได้เป็น 2 กลุ่มกว้าง ๆ ได้แก่ ภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน และภาษาสันสกฤตผสม

ภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน

แก้เกิดขึ้นจากการวางกฎเกณฑ์ของภาษาสันสกฤตให้มีแบบแผนที่แน่นอนในสมัยต่อมา โดยนักปราชญ์ชื่อ ปาณินิตามประวัติเล่าว่าเป็นผู้เกิดในตระกูลพราหมณ์ แคว้นคันธาระราว 57 ปีก่อนพุทธปรินิพพาน บางกระแสว่าเกิดราว พ.ศ. 143 ปาณินิได้ศึกษาภาษาในคัมภีร์พระเวทจนสามารถหาหลักเกณฑ์ของภาษานั้นได้ จึงจัดรวบรวมขึ้นเป็นหมวดหมู่ เรียบเรียงเป็นตำราไวยากรณ์ขึ้น 8 บทให้ชื่อว่า อัษฏาธยายี มีสูตรเป็นกฎเกณฑ์อธิบายโครงสร้างของคำอย่างชัดเจน นักวิชาการสมัยใหม่มีความเห็นว่า วิธีการศึกษาและอธิบายภาษาของปาณินิเป็นวิธีวรรณนา คือศึกษาและอธิบายตามที่ได้สังเกตเห็นจริง มิได้เรียบเรียงขึ้นตามความเชื่อส่วนตัว มิได้เรียบเรียงขึ้นตามหลักปรัชญา คัมภีร์อัษฏาธยายีจึงได้รับการยกย่องว่าเป็นตำราไวยากรณ์เล่มแรกที่ศึกษาภาษาในแนววิทยาศาสตร์และวิเคราะห์ภาษาได้สมบูรณ์ที่สุด[ต้องการอ้างอิง] ความสมบูรณ์ของตำราเล่มนี้ทำให้เกิดความเชื่อในหมู่พราหมณ์ว่า ตำราไวยากรณ์สันสกฤตหรือปาณินิรจนานี้ สำเร็จได้ด้วยอำนาจพระศิวะ อย่างไรก็ตาม นักภาษาศาสตร์เชื่อว่าการวางแบบแผนอย่างเคร่งครัดของปาณินิ ถือเป็นสาเหตุหนึ่งที่ทำให้ภาษาสันสกฤตต้องกลายเป็นภาษาตายอย่างรวดเร็วก่อนเวลาอันควร[ต้องการอ้างอิง] เพราะทำให้สันสกฤตกลายเป็นภาษาที่ถูกจำกัดขอบเขต (a fettered language) ด้วยกฎเกณฑ์ทางไวยากรณ์ที่เคร่งครัดและสลับซับซ้อน ภาษาสันสกฤตที่ได้ร้บการปรับปรุงแก้ไขหลักเกณฑ์ให้ดีขึ้นโดยปาณินินี้เรียกอีกชื่อหนึ่งว่า "เลากิกภาษา" หมายถึงภาษาที่ใช้กับสิ่งที่เป็นไปในทางโลก

ภาษาสันสกฤตผสม

แก้ภาษาสันสกฤตผสม (Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit or Mixed Sanskrit) เป็นภาษาสันสกฤตที่นักวิชาการบางกลุ่มได้จัดไว้เป็นพิเศษ เนื่องจากมีความแตกต่างจากภาษาพระเวทและภาษาสันสกฤตแบบแผน (ตันติสันสกฤต) ภาษาสันสกฤตแบบผสมนี้คือภาษาที่ใช้บันทึกวรรณคดีสันสกฤตทางพระพุทธศาสนา ทั้งในนิกาย สรรวาสติวาท และ มหายาน ภาษาสันสกฤตชนิดนี้คาดว่าเกิดขึ้นในราวพุทธศตวรรษที่ 3–4 นักปราชญ์บางท่านถือว่าเกิดขึ้นร่วมสมัยกับตันติสันสกฤต คือในปลายสมัยพระเวทและต้นของยุคตันติสันสกฤต โดยปรากฏอยู่โดยส่วนมากในวรรณกรรมของพระพุทธศาสนามหายาน เช่น ลลิตวิสฺตร ลงฺกาวตารสูตฺร ปฺรชฺญาปารมิตา สทฺธรฺมปุณฺฑรีกสูตฺร และศาสตร์อันเป็นคำอธิบายหลักพุทธปรัชญาและตรรกวิทยา เช่น มธฺยมิกการิกา อภิธรฺมโกศ มหาปฺรชฺญาปารมิตาศาสฺตฺร มธฺยานฺตานุคมศาสฺตฺร เป็นต้น

ไวยากรณ์ของภาษาสันสกฤตมีความซับซ้อนมากกว่าหลาย ๆ ภาษา โดยเฉพาะกฎเกณฑ์การสนธิ แต่ก็นับว่ามีความสอดคล้องกับหลายภาษาในกลุ่มภาษาอินโด-ยูโรเปียน เช่น กรีกหรือละติน อย่างที่กล่าวมาข้างต้น อย่างไรก็ตาม ไวยากรณ์สันสกฤตอาจเทียบเคียงได้กับของภาษาบาลี แต่ยังมีความยุ่งยากและซับซ้อนกว่าพอสมควร

ภาษาสันสกฤตมีรูปอักษร 48 ตัว แบ่งเป็นพยัญชนะ 34 ตัว สระ 14 ตัว

สระ

แก้| รูปเดี่ยว | ไอเอเอสที/ ไอเอสโอ |

สัทอักษร สากล |

รูปเดี่ยว | ไอเอเอสที/ ไอเอสโอ |

สัทอักษร สากล | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| กัณฐยะ (เพดานอ่อน/ช่องคอ) |

अ | a | /ɐ/ | आ | ā | /ɑː/ | ||

| ตาลวยะ (เพดานแข็ง) |

इ | i | /i/ | ई | ī | /iː/ | ||

| โอษฐยะ (ริมฝีปาก) |

उ | u | /u/ | ऊ | ū | /uː/ | ||

| มูรธันยะ (ปลายลิ้นม้วน) |

ऋ | ṛ/r̥ | /r̩/ | ॠ | ṝ/r̥̄ | /r̩ː/ | ||

| ทันตยะ (ฟัน) |

ऌ | ḷ/l̥ | /l̩/ | (ॡ) | (ḹ/l̥̄)[e] | /l̩ː/ | ||

| กัณฐตาลวยะ (เพดานแข็ง-คอหอย) |

ए | e/ē | /eː/ | ऐ | ai | /ɑj/ | ||

| กัณโฐษฐยะ (ริมฝีปาก-คอหอย) |

ओ | o/ō | /oː/ | औ | au | /ɑw/ | ||

| (หน่วยเสียงพยัญชนะย่อย) | अं | aṃ/aṁ | /ɐ̃/ | अः | aḥ | /ɐh/ |

สระ 14 ตัวได้แก่ อะ อา อิ อี อุ อู เอ โอ ฤ ฤๅ ฦ ฦๅ ไอ เอา แบ่งได้เป็น 3 ขั้นคือ ขั้นปกติ ขั้นคุณ ขั้นพฤทธิ์

พยัญชนะ

แก้| สปรรศะ (หยุด) |

อนุนาสิกะ (นาสิก) |

อันตัสถะ (เปิด) |

อูษมัน/saṃgharṣhī (เสียดแทรก) | ||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ความก้อง → | อโฆษะ | โฆษะ | อโฆษะ | ||||||||||||||||||

| การออกเสียงพ่นลม → | อัลปปราณะ | มหาปราณะ | อัลปปราณะ | มหาปราณะ | อัลปปราณะ | มหาปราณะ | |||||||||||||||

| กัณฐยะ (เพดานอ่อน/ช่องคอ) |

क | ka | /k/ | ख | kha | /kʰ/ | ग | ga | /g/ | घ | gha | /gʱ/ | ङ | ṅa | /ŋ/ | ह | ha | /ɦ/ | |||

| ตาลวยะ (เพดานแข็ง) |

च | ca | /t͡ɕ/ | छ | cha | /t͡ɕʰ/ | ज | ja | /d͡ʑ/ | झ | jha | /d͡ʑʱ/ | ञ | ña | /ɲ/ | य | ya | /j/ | श | śa | /ɕ/ |

| มูรธันยะ (ปลายลิ้นม้วน) |

ट | ṭa | /ʈ/ | ठ | ṭha | /ʈʰ/ | ड | ḍa | /ɖ/ | ढ | ḍha | /ɖʱ/ | ण | ṇa | /ɳ/ | र | ra | /ɾ/ | ष | ṣa | /ʂ/ |

| ทันตยะ (ฟัน) |

त | ta | /t̪/ | थ | tha | /tʰ/ | द | da | /d̪/ | ध | dha | /d̪ʱ/ | न | na | /n̪/ | ल | la | /l̪/ | स | sa | /s̪/ |

| โอษฐยะ (ริมฝีปาก) |

प | pa | /p/ | फ | pha | /pʰ/ | ब | ba | /b/ | भ | bha | /bʱ/ | म | ma | /m/ | व | va | /ʋ/ | |||

พยัญชนะ 34 ตัวแบ่งเป็น 2 กลุ่มคือ

- พยัญชนะวรรค แบ่งเป็น 5 วรรค รวม 25 ตัว คือ

- วรรค กะ เสียงเกิดที่คอ ได้แก่ ก ข ค ฆ ง

- วรรค จะ เสียงเกิดที่เพดาน ได้แก่ จ ฉ ช ฌ ญ

- วรรค ฏะ เสียงเกิดที่ปุ่มเหงือก ได้แก่ ฏ ฐ ฑ ฒ ณ

- วรรค ตะ เสียงเกิดที่ฟัน ได้แก่ ต ถ ท ธ น

- วรรค ปะ เสียงเกิดที่ริมฝีปาก ได้แก่ ป ผ พ ภ ม

- พยัญชนะอวรรค 9 ตัว แบ่งเป็น

- เสียงกึ่งสระ ได้แก่ ย เสียงเกิดที่เพดาน ร เสียงเกิดที่ปุ่มเหงือก ล เสียงเกิดที่ฟัน ว เสียงเกิดที่ริมฝีปาก

- เสียงเสียดแทรก ได้แก่ ศ เสียงเกิดที่เพดาน ษ เสียงเกิดที่ปุ่มเหงือก ส เสียงเกิดที่ฟัน

- เสียงหนักมีลม ได้ แก่ ห

- ฬ และ อัง (อํ)

พยัญชนะไทยที่เขียนลำพังโดยไม่มีสระอื่นถือว่ามีเสียงอะ ถ้ามีจุดข้างล่างถือว่าไม่มีเสียงสระ

คำนาม

แก้ภาษาสันสกฤตเป็นภาษาที่มีการลงวิภัตติปัจจัย แจกนามได้ถึง 8 การก [แบ่งเป็นสามพจน์ (เอกพจน์, ทวิพจน์, พหูพจน์) และสามเพศ (สตรีลิงค์, ปุลลิงก์ และนปุงสกลิงก์)]

คำกริยา

แก้สำหรับกริยา (ธาตุ) ในภาษาสันสกฤตนั้นมีความซับซ้อนยิ่งกว่าคำนาม กล่าวคือ จำแนกกริยาไว้ถึง 10 คณะ แต่ละคณะมีการเปลี่ยนรูป (เสียง) แตกต่างกันไป กริยาเหล่านี้จะแจกรูปตามประธาน 3 แบบ (ปฐมบุรุษ, มัธยมบุรุษ และอุตมบุรุษ) นอกจากนี้กริยายังต้องแจกรูปตามกาล (tense) 6 ชนิด และตามมาลา (mood) 4 ชนิด

อักษร

แก้ภาษาสันสกฤตไม่มีอักษรสำหรับเขียนชนิดใดชนิดหนึ่งโดยเฉพาะ และก็คล้ายกับภาษาอื่นหลายภาษา นั่นคือสามารถเขียนได้ด้วยอักษรหลายชนิด อักษรเก่าแก่ที่ใช้เขียนภาษาสันสกฤตมีหลายชนิดด้วยกัน เช่น อักษรขโรษฐี (Kharosthī) หรืออักษรคานธารี (Gāndhārī) นอกจากนี้ยังมีอักษรพราหมี (อักษรทั้งสองแบบพบได้ที่จารึกบนเสาอโศก) อักษรรัญชนา ซึ่งนิยมใช้จารึกคัมภีร์ทางพระพุทธศาสนาในอินเดียเหนือและเนปาล รวมถึง อักษรสิทธัม ซึ่งใช้บันทึกคัมภีร์พุทธศาสนารวมถึงบทสวดภาษาสันสกฤตในประเทศจีนและญี่ปุ่นโดยเฉพาะในนิกายมนตรยาน อย่างไรก็ตาม โดยทั่วไปนิยมเขียนภาษาสันสกฤตด้วยอักษรเทวนาครี (Devanāgarī) ส่วนอักษรอื่น ๆ เป็นความนิยมในแต่ละท้องถิ่น ทั้งนี้เนื่องจากอักษรที่ใช้ในอินเดีย มักจะเป็นตระกูลเดียวกัน จึงสามารถดัดแปลงและถ่ายทอด (transliteration) ระหว่างชุดอักษรได้ง่าย

แม้กระทั่งในเอเชียตะวันออกเฉียงใต้ ยังมีจารึกภาษาสันสกฤตที่ใช้ อักษรปัลลวะ อักษรขอม นอกจากนี้ชาวยุโรปยังใช้อักษรโรมันเขียนภาษาสันสกฤต โดยเพิ่มเติมจุดและเครื่องหมายเล็กน้อยเท่านั้น

หมายเหตุ

แก้- ↑ 1.0 1.1 "In conclusion, there are strong systemic and paleographic indications that the Brahmi script derived from a Semitic prototype, which, mainly on historical grounds, is most likely to have been Aramaic. However, the details of this problem remain to be worked out, and in any case, it is unlikely that a complete letter-by-letter derivation will ever be possible; for Brahmi may have been more of an adaptation and remodeling, rather than a direct derivation, of the presumptive Semitic prototype, perhaps under the influence of a preexisting Indian tradition of phonetic analysis. However, the Semitic hypothesis 1s not so strong as to rule out the remote possibility that further discoveries could drastically change the picture. In particular, a relationship of some kind, probably partial or indirect, with the protohistoric Indus Valley script should not be considered entirely out of the question." Salomon 1998, p. 30

- ↑ "dhārayan·brāhmaṇam rupam·ilvalaḥ saṃskṛtam vadan..." - รามายณะ 3.10.54 - กล่าวกันว่าเป็นจุดแรกที่มีการใช้คำว่า สันสกฤต ในการอ้างถึงภาษานี้

- ↑ ขนบไวยากรณ์ภาษาสันสกฤตเป็นที่มาขั้นท้ายสุดของแนวคิดเรื่องเลขศูนย์ ซึ่งเมื่อนำไปใช้ในระบบเลขอาหรับแล้ว ทำให้เราก้าวข้ามสัญกรณ์เลขโรมันที่ยุ่งยากไปได้[25]

- ↑ ภาษาสันสกฤตเขียนด้วยอักษรหลายชุด เสียงในช่องสีเทาไม่จัดเป็นหน่วยเสียง

- ↑ ḹ ไม่ใช่เสียงจริงในภาษาสันสกฤต แต่เป็นธรรมเนียมการแสดงรูปเขียนที่รวมอยู่ในรูปเขียนสระเพื่อรักษาสมมาตรของคู่อักษรสั้น-ยาวมากกว่า[43]

- ↑ ภาษาสันสกฤตเขียนด้วยอักษรหลายชุด เสียงในช่องสีเทาไม่จัดเป็นหน่วยเสียง

อ้างอิง

แก้- ↑ Mascaró, Juan (2003). The Bhagavad Gita. Penguin. pp. 13 ff. ISBN 978-0-14-044918-1.

The Bhagawad Gita, an intensely spiritual work, that forms one of the cornerstones of the Hindu faith, and is also one of the masterpieces of Sanskrit poetry. (from the backcover)

- ↑ Besant, Annie (trans) (1922). The Bhagavad-gita; or, The Lord's Song, with text in Devanagari, and English translation. Madras: G. E. Natesan & Co.

प्रवृत्ते शस्त्रसम्पाते धनुरुद्यम्य पाण्डवः ॥ २० ॥

Then, beholding the sons of Dhritarâshtra standing arrayed, and flight of missiles about to begin, ... the son of Pându, took up his bow,(20)

हृषीकेशं तदा वाक्यमिदमाह महीपते । अर्जुन उवाच । ...॥ २१ ॥

And spake this word to Hrishîkesha, O Lord of Earth: Arjuna said: ... - ↑ Radhakrishnan, S. (1948). The Bhagavadgītā: With an introductory essay, Sanskrit text, English translation, and notes. London, UK: George Allen and Unwin Ltd. p. 86.

... pravyite Sastrasampate

dhanur udyamya pandavah (20)

Then Arjuna, ... looked at the sons of Dhrtarastra drawn up in battle order; and as the flight of missiles (almost) started, he took up his bow.

hystkesam tada vakyam

idam aha mahipate ... (21)

And, O Lord of earth, he spoke this word to Hrsikesha (Krsna): ... - ↑ Uta Reinöhl (2016). Grammaticalization and the Rise of Configurationality in Indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press. pp. xiv, 1–16. ISBN 978-0-19-873666-0.

- ↑ Colin P. Masica 1993, p. 55: "Thus Classical Sanskrit, fixed by Panini’s grammar in probably the fourth century BC on the basis of a class dialect (and preceding grammatical tradition) of probably the seventh century BC, had its greatest literary flowering in the first millennium A D and even later, much of it therefore a full thousand years after the stage of the language it ostensibly represents."

- ↑ 6.0 6.1 Jain, Dhanesh (2007). "Sociolinguistics of the Indo-Aryan languages". ใน George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (บ.ก.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 47–66, 51. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

In the history of Indo-Aryan, writing was a later development and its adoption has been slow even in modern times. The first written word comes to us through Asokan inscriptions dating back to the third century BC. Originally, Brahmi was used to write Prakrit (MIA); for Sanskrit (OIA) it was used only four centuries later (Masica 1991: 135). The MIA traditions of Buddhist and Jain texts show greater regard for the written word than the OIA Brahminical tradition, though writing was available to Old Indo-Aryans.

- ↑ 7.0 7.1 Salomon, Richard (2007). "The Writing Systems of the Indo-Aryan Languages". ใน George Cardona; Dhanesh Jain (บ.ก.). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. pp. 67–102. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

Although in modern usage Sanskrit is most commonly written or printed in Nagari, in theory, it can be represented by virtually any of the main Brahmi-based scripts, and in practice it often is. Thus scripts such as Gujarati, Bangla, and Oriya, as well as the major south Indian scripts, traditionally have been and often still are used in their proper territories for writing Sanskrit. Sanskrit, in other words, is not inherently linked to any particular script, although it does have a special historical connection with Nagari.

- ↑ "Constitution of the Republic of South Africa, 1996 - Chapter 1: Founding Provisions". www.gov.za. สืบค้นเมื่อ 6 December 2014.

- ↑ Cardona, George; Luraghi, Silvia (2018). "Sanskrit". ใน Bernard Comrie (บ.ก.). The World's Major Languages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 497–. ISBN 978-1-317-29049-0.

Sanskrit (samskrita- 'adorned, purified') ... It is in the Ramayana that the term saṃskṛta- is encountered probably for the first time with reference to the language.

- ↑ Wright, J.C. (1990). "Reviewed Works: Pāṇini: His Work and Its Traditions. Vol. I. Background and Introduction by George Cardona; Grammaire sanskrite pâninéenne by Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat". Bulletin of the School of Oriental and African Studies, University of London. Cambridge University Press. 53 (1): 152–154. doi:10.1017/S0041977X0002156X. JSTOR 618999.

The first reference to "Sanskrit" in the context of language is in the Ramayana, Book 5 (Sundarkanda), Canto 28, Verse 17: अहं ह्यतितनुश्चैव वनरश्च विशेषतः // वाचंचोदाहरिष्यामि मानुषीमिह संस्कृताम् // १७ // Hanuman says, "First, my body is very subtle, second I am a monkey. Especially as a monkey, I will use here the human-appropriate Sanskrit speech / language.

- ↑ Apte, Vaman Shivaram (1957). Revised and enlarged edition of Prin. V.S. Apte's The practical Sanskrit-English Dictionary. Poona: Prasad Prakashan. p. 1596.

from संस्कृत saṃskṛitə past passive participle: Made perfect, refined, polished, cultivated. -तः -tah A word formed regularly according to the rules of grammar, a regular derivative. -तम् -tam Refined or highly polished speech, the Sanskṛit language; संस्कृतं नाम दैवी वागन्वाख्याता महर्षिभिः ("named sanskritam the divine language elaborated by the sages") from Kāvyadarśa.1. 33. of Daṇḍin

- ↑ Roger D. Woodard (2008). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1.

The earliest form of this 'oldest' language, Sanskrit, is the one found in the ancient Brahmanic text called the Rigveda, composed c. 1500 BC. The date makes Sanskrit one of the three earliest of the well-documented languages of the Indo-European family – the other two being Old Hittite and Myceanaean Greek – and, in keeping with its early appearance, Sanskrit has been a cornerstone in the reconstruction of the parent language of the Indo-European family – Proto-Indo-European.

- ↑ Bauer, Brigitte L. M. (2017). Nominal Apposition in Indo-European: Its forms and functions, and its evolution in Latin-romance. De Gruyter. pp. 90–92. ISBN 978-3-11-046175-6. For detailed comparison of the languages, see pp. 90–126.

- ↑ Ramat, Anna Giacalone; Ramat, Paolo (2015). The Indo-European Languages. Routledge. pp. 26–31. ISBN 978-1-134-92187-4.

- ↑ Dyson, Tim (2018). A Population History of India: From the First Modern People to the Present Day. Oxford University Press. pp. 14–15. ISBN 978-0-19-882905-8.

Although the collapse of the Indus valley civilization is no longer believed to have been due to an ‘Aryan invasion’ it is widely thought that, at roughly the same time, or perhaps a few centuries later, new Indo-Aryan-speaking people and influences began to enter the subcontinent from the north-west. Detailed evidence is lacking. Nevertheless, a predecessor of the language that would eventually be called Sanskrit was probably introduced into the north-west sometime between 3,900 and 3,000 years ago. This language was related to one then spoken in eastern Iran; and both of these languages belonged to the Indo-European language family.

- ↑ Pinkney, Andrea Marion (2014). "Revealing the Vedas in 'Hinduism': Foundations and issues of interpretation of religions in South Asian Hindu traditions". ใน Bryan S. Turner; Oscar Salemink (บ.ก.). Routledge Handbook of Religions in Asia. Routledge. pp. 38–. ISBN 978-1-317-63646-5.

According to Asko Parpola, the Proto-Indo-Aryan civilization was influenced by two external waves of migrations. The first group originated from the southern Urals (c. 2100 BCE) and mixed with the peoples of the Bactria-Margiana Archaeological Complex (BMAC); this group then proceeded to South Asia, arriving around 1900 BCE. The second wave arrived in northern South Asia around 1750 BCE and mixed with the formerly arrived group, producing the Mitanni Aryans (c. 1500 BCE), a precursor to the peoples of the Ṛgveda. Michael Witzel has assigned an approximate chronology to the strata of Vedic languages, arguing that the language of the Ṛgveda changed through the beginning of the Iron Age in South Asia, which started in the Northwest (Punjab) around 1000 BCE. On the basis of comparative philological evidence, Witzel has suggested a five-stage periodization of Vedic civilization, beginning with the Ṛgveda. On the basis of internal evidence, the Ṛgveda is dated as a late Bronze Age text composed by pastoral migrants with limited settlements, probably between 1350 and 1150 BCE in the Punjab region.

- ↑ Michael C. Howard 2012, p. 21

- ↑ Pollock, Sheldon (2006). The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press. p. 14. ISBN 978-0-520-24500-6.

Once Sanskrit emerged from the sacerdotal environment ... it became the sole medium by which ruling elites expressed their power ... Sanskrit probably never functioned as an everyday medium of communication anywhere in the cosmopolis—not in South Asia itself, let alone Southeast Asia ... The work Sanskrit did do ... was directed above all toward articulating a form of ... politics ... as celebration of aesthetic power.

- ↑ Burrow 1973, pp. 62–64.

- ↑ Cardona, George; Luraghi, Silvia (2018). "Sanskrit". ใน Bernard Comrie (บ.ก.). The World's Major Languages. Taylor & Francis. pp. 497–. ISBN 978-1-317-29049-0.

Sanskrit (samskrita- 'adorned, purified') refers to several varieties of Old Indo-Aryan whose most archaic forms are found in Vedic texts: the Rigveda (Ṛgveda), Yajurveda, Sāmveda, Atharvaveda, with various branches.

- ↑ Alfred C. Woolner (1986). Introduction to Prakrit. Motilal Banarsidass. pp. 3–4. ISBN 978-81-208-0189-9.

If in 'Sanskrit' we include the Vedic language and all dialects of the Old Indian period, then it is true to say that all the Prakrits are derived from Sanskrit. If on the other hand 'Sanskrit' is used more strictly of the Panini-Patanjali language or 'Classical Sanskrit,' then it is untrue to say that any Prakrit is derived from Sanskrit, except that Sauraseni, the Midland Prakrit, is derived from the Old Indian dialect of the Madhyadesa on which Classical Sanskrit was mainly based.

- ↑ Lowe, John J. (2015). Participles in Rigvedic Sanskrit: The syntax and semantics of adjectival verb forms. Oxford University Press. pp. 1–2. ISBN 978-0-19-100505-3.

It consists of 1,028 hymns (suktas), highly crafted poetic compositions originally intended for recital during rituals and for the invocation of and communication with the Indo-Aryan gods. Modern scholarly opinion largely agrees that these hymns were composed between around 1500 BCE and 1200 BCE, during the eastward migration of the Indo-Aryan tribes from the mountains of what is today northern Afghanistan across the Punjab into north India.

- ↑ Witzel, Michael (2006). "Early Loan Words in Western Central Asia: Indicators of Substrate Populations, Migrations, and Trade Relations". ใน Victor H. Mair (บ.ก.). Contact And Exchange in the Ancient World. University of Hawaii Press. pp. 158–190, 160. ISBN 978-0-8248-2884-4.

The Vedas were composed (roughly between 1500-1200 and 500 BCE) in parts of present-day Afghanistan, northern Pakistan, and northern India. The oldest text at our disposal is the Rgveda (RV); it is composed in archaic Indo-Aryan (Vedic Sanskrit).

- ↑ Shulman, David (2016). Tamil. Harvard University Press. pp. 17–19. ISBN 978-0-674-97465-4.

(p. 17) Similarly, we find a large number of other items relating to flora and fauna, grains, pulses, and spices—that is, words that we might expect to have made their way into Sanskrit from the linguistic environment of prehistoric or early-historic India. ... (p. 18) Dravidian certainly influenced Sanskrit phonology and syntax from early on ... (p 19) Vedic Sanskrit was in contact, from very ancient times, with speakers of Dravidian languages, and that the two language families profoundly influenced one another.

- ↑ 25.0 25.1 Evans, Nicholas (2009). Dying Words: Endangered languages and what they have to tell us. John Wiley & Sons. pp. 27–. ISBN 978-0-631-23305-3.

- ↑ Glenn Van Brummelen (2014). "Arithmetic". ใน Thomas F. Glick; Steven Livesey; Faith Wallis (บ.ก.). Medieval Science, Technology, and Medicine: An Encyclopedia. Routledge. pp. 46–48. ISBN 978-1-135-45932-1.

The story of the growth of arithmetic from the ancient inheritance to the wealth passed on to the Renaissance is dramatic and passes through several cultures. The most groundbreaking achievement was the evolution of a positional number system, in which the position of a digit within a number determines its value according to powers (usually) of ten (e.g., in 3,285, the "2" refers to hundreds). Its extension to include decimal fractions and the procedures that were made possible by its adoption transformed the abilities of all who calculated, with an effect comparable to the modern invention of the electronic computer. Roughly speaking, this began in India, was transmitted to Islam, and then to the Latin West.

- ↑ Lowe, John J. (2017). Transitive Nouns and Adjectives: Evidence from Early Indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press. p. 58. ISBN 978-0-19-879357-1.

The term ‘Epic Sanskrit’ refers to the language of the two great Sanskrit epics, the Mahābhārata and the Rāmāyaṇa. ... It is likely, therefore, that the epic-like elements found in Vedic sources and the two epics that we have are not directly related, but that both drew on the same source, an oral tradition of storytelling that existed before, throughout, and after the Vedic period.

- ↑ Lowe, John J. (2017). Transitive Nouns and Adjectives: Evidence from Early Indo-Aryan. Oxford University Press. p. 53. ISBN 978-0-19-879357-1.

The desire to preserve understanding and knowledge of Sanskrit in the face of ongoing linguistic change drove the development of an indigenous grammatical tradition, which culminated in the composition of the Aṣṭādhyāyī, attributed to the grammarian Pāṇini, no later than the early fourth century BCE. In subsequent centuries, Sanskrit ceased to be learnt as a native language, and eventually ceased to develop as living languages do, becoming increasingly fixed according to the prescriptions of the grammatical tradition.

- ↑ Gazzola, Michele; Wickström, Bengt-Arne (2016). The Economics of Language Policy. MIT Press. pp. 469–. ISBN 978-0-262-03470-8.

The Eighth Schedule recognizes India's national languages as including the major regional languages as well as others, such as Sanskrit and Urdu, which contribute to India's cultural heritage. ... The original list of fourteen languages in the Eighth Schedule at the time of the adoption of the Constitution in 1949 has now grown to twenty-two.

- ↑ Groff, Cynthia (2017). The Ecology of Language in Multilingual India: Voices of Women and Educators in the Himalayan Foothills. Palgrave Macmillan UK. pp. 58–. ISBN 978-1-137-51961-0.

As Mahapatra says: “It is generally believed that the significance for the Eighth Schedule lies in providing a list of languages from which Hindi is directed to draw the appropriate forms, style and expressions for its enrichment” ... Being recognized in the Constitution, however, has had significant relevance for a language's status and functions.

- ↑ "Indian village where people speak in Sanskrit". BBC News (ภาษาอังกฤษแบบบริติช). 22 December 2014. สืบค้นเมื่อ 30 September 2020.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 Sreevastan, Ajai (10 August 2014). "Where are the Sanskrit speakers?". The Hindu. Chennai. สืบค้นเมื่อ 11 October 2020.

Sanskrit is also the only scheduled language that shows wide fluctuations — rising from 6,106 speakers in 1981 to 49,736 in 1991 and then falling dramatically to 14,135 speakers in 2001. “This fluctuation is not necessarily an error of the Census method. People often switch language loyalties depending on the immediate political climate,” says Prof. Ganesh Devy of the People's Linguistic Survey of India. ... Because some people “fictitiously” indicate Sanskrit as their mother tongue owing to its high prestige and Constitutional mandate, the Census captures the persisting memory of an ancient language that is no longer anyone's real mother tongue, says B. Mallikarjun of the Center for Classical Language. Hence, the numbers fluctuate in each Census. ... “Sanskrit has influence without presence,” says Devy. “We all feel in some corner of the country, Sanskrit is spoken.” But even in Karnataka's Mattur, which is often referred to as India's Sanskrit village, hardly a handful indicated Sanskrit as their mother tongue.

- ↑ Ruppel, A. M. (2017). The Cambridge Introduction to Sanskrit. Cambridge University Press. p. 2. ISBN 978-1-107-08828-3.

The study of any ancient (or dead) language is faced with one main challenge: ancient languages have no native speakers who could provide us with examples of simple everyday speech

- ↑ Distribution of the 22 Scheduled Languages – India / States / Union Territories – Sanskrit (PDF), Census of India, 2011, p. 30, สืบค้นเมื่อ 4 October 2020

- ↑ Annamalai, E. (2008). "Contexts of multilingualism". ใน Braj B. Kachru; Yamuna Kachru; S. N. Sridhar (บ.ก.). Language in South Asia. Cambridge University Press. pp. 223–. ISBN 978-1-139-46550-2.

Some of the migrated languages ... such as Sanskrit and English, remained primarily as a second language, even though their native speakers were lost. Some native languages like the language of the Indus valley were lost with their speakers, while some linguistic communities shifted their language to one or other of the migrants’ languages.

- ↑ Angus Stevenson & Maurice Waite 2011, p. 1275

- ↑ Shlomo Biderman 2008, p. 90.

- ↑ Will Durant 1963, p. 406.

- ↑ Sir Monier Monier-Williams (2005). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Motilal Banarsidass. p. 1120. ISBN 978-81-208-3105-6.

- ↑ Louis Renou & Jagbans Kishore Balbir 2004, pp. 1–2.

- ↑ จำลอง สารพัดนึก. ไวยากรณ์สันสกฤต 1. กรุงเทพฯ:มหาจุฬาลงกรณราชวิทยาลัย.2544

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 Robert P. Goldman & Sally J Sutherland Goldman 2002, pp. 13–19.

- ↑ Salomon 2007, p. 75.

บรรณานุกรม

แก้- H. W. Bailey (1955). "Buddhist Sanskrit". The Journal of the Royal Asiatic Society of Great Britain and Ireland. Cambridge University Press. 87 (1/2): 13–24. doi:10.1017/S0035869X00106975. JSTOR 25581326.

- Banerji, Sures (1989). A Companion to Sanskrit Literature: Spanning a period of over three thousand years, containing brief accounts of authors, works, characters, technical terms, geographical names, myths, legends, and several appendices. Delhi: Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-0063-2.

- Guy L. Beck (1995). Sonic Theology: Hinduism and Sacred Sound. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1261-1.

- Guy L. Beck (2006). Sacred Sound: Experiencing Music in World Religions. Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press. ISBN 978-0-88920-421-8.

- Robert S.P. Beekes (2011). Comparative Indo-European Linguistics: An introduction (2nd ed.). John Benjamins Publishing. ISBN 978-90-272-8500-3.

- Benware, Wilbur (1974). The Study of Indo-European Vocalism in the 19th Century: From the Beginnings to Whitney and Scherer: A Critical-Historical Account. Benjamins. ISBN 978-90-272-0894-1.

- Shlomo Biderman (2008). Crossing Horizons: World, Self, and Language in Indian and Western Thought. Columbia University Press. ISBN 978-0-231-51159-9.

- Claire Bowern; Bethwyn Evans (2015). The Routledge Handbook of Historical Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-317-74324-8.

- John L. Brockington (1998). The Sanskrit Epics. BRILL Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-10260-6.

- Johannes Bronkhorst (1993). "Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit: The Original Language". Aspects of Buddhist Sanskrit: Proceedings of the International Symposium on the Language of Sanskrit Buddhist Texts, 1–5 Oct. 1991. Sarnath. pp. 396–423. ISBN 978-81-900149-1-5.

- Bryant, Edwin (2001). The Quest for the Origins of Vedic Culture: The Indo-Aryan Migration Debate. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-513777-4.

- Edwin Francis Bryant; Laurie L. Patton (2005). The Indo-Aryan Controversy: Evidence and Inference in Indian History. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-7007-1463-6.

- Burrow, Thomas (1973). The Sanskrit Language (3rd, revised ed.). London: Faber & Faber.

- Burrow, Thomas (2001). The Sanskrit Language. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-1767-2.

- Robert E. Buswell Jr.; Donald S. Lopez Jr. (2013). The Princeton Dictionary of Buddhism. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-1-4008-4805-8.

- Cardona, George (1997). Pāṇini - His work and its traditions. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 81-208-0419-8.

- George Cardona (2012). Sanskrit Language. Encyclopaedia Britannica.

- James Clackson (18 October 2007). Indo-European Linguistics: An Introduction. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-139-46734-6.

- Coulson, Michael (1992). Richard Gombrich; James Benson (บ.ก.). Sanskrit : an introduction to the classical language (2nd, revised by Gombrich and Benson ed.). Random House. ISBN 978-0-340-56867-5. OCLC 26550827.

- Michael Coulson; Richard Gombrich; James Benson (2011). Complete Sanskrit: A Teach Yourself Guide. Mcgraw-Hill. ISBN 978-0-07-175266-4.

- Harold G. Coward (1990). Karl Potter (บ.ก.). The Philosophy of the Grammarians, in Encyclopedia of Indian Philosophies. Vol. 5. Princeton University Press. ISBN 978-81-208-0426-5.

- Suniti Kumar Chatterji (1957). "Indianism and Sanskrit". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 38 (1/2): 1–33. JSTOR 44082791.

- Peter T. Daniels (1996). The World's Writing Systems. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-507993-7.

- Deshpande, Madhav (2011). "Efforts to vernacularize Sanskrit: Degree of success and failure". ใน Joshua Fishman; Ofelia Garcia (บ.ก.). Handbook of Language and Ethnic Identity: The success-failure continuum in language and ethnic identity efforts. Vol. 2. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-983799-1.

- Will Durant (1963). Our oriental heritage. Simon & Schuster. ISBN 978-1567310122.

- Eltschinger, Vincent (2017). "Why Did the Buddhists Adopt Sanskrit?". Open Linguistics. 3 (1). doi:10.1515/opli-2017-0015. ISSN 2300-9969.

- J. Filliozat (1955). "Sanskrit as Language of Communication". Annals of the Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. Bhandarkar Oriental Research Institute. 36 (3/4): 179–189. JSTOR 44082954.

- Filliozat, Pierre-Sylvain (2004), "Ancient Sanskrit Mathematics: An Oral Tradition and a Written Literature", ใน Chemla, Karine; Cohen, Robert S.; Renn, Jürgen; และคณะ (บ.ก.), History of Science, History of Text (Boston Series in the Philosophy of Science), Dordrecht: Springer Netherlands, pp. 360–375, doi:10.1007/1-4020-2321-9_7, ISBN 978-1-4020-2320-0

- Pierre-Sylvain Filliozat (2000). The Sanskrit Language: An Overview : History and Structure, Linguistic and Philosophical Representations, Uses and Users. Indica. ISBN 978-81-86569-17-7.

- Benjamin W. Fortson, IV (2011). Indo-European Language and Culture: An Introduction. John Wiley & Sons. ISBN 978-1-4443-5968-8.

- Robert P. Goldman; Sally J Sutherland Goldman (2002). Devavāṇīpraveśikā: An Introduction to the Sanskrit Language. Center for South Asia Studies, University of California Press.

- Thomas V. Gamkrelidze; Vjaceslav V. Ivanov (2010). Indo-European and the Indo-Europeans: A Reconstruction and Historical Analysis of a Proto-Language and Proto-Culture. Part I: The Text. Part II: Bibliography, Indexes. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-081503-0.

- Thomas V. Gamkrelidze; V. V. Ivanov (1990). "The Early History of Indo-European Languages". Scientific American. Nature America. 262 (3): 110–117. Bibcode:1990SciAm.262c.110G. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican0390-110. JSTOR 24996796.

- Jack Goody (1987). The Interface Between the Written and the Oral. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-33794-6.

- Reinhold Grünendahl (2001). South Indian Scripts in Sanskrit Manuscripts and Prints: Grantha Tamil, Malayalam, Telugu, Kannada, Nandinagari. Otto Harrassowitz Verlag. ISBN 978-3-447-04504-9.

- Houben, Jan (1996). Ideology and status of Sanskrit: contributions to the history of the Sanskrit language. Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-10613-0.

- Hanneder, J. (2002). "On 'The Death of Sanskrit'". Indo-Iranian Journal. Brill Academic Publishers. 45 (4): 293–310. doi:10.1023/a:1021366131934. S2CID 189797805.

- Hock, Hans Henrich (1983). Kachru, Braj B (บ.ก.). "Language-death phenomena in Sanskrit: grammatical evidence for attrition in contemporary spoken Sanskrit". Studies in the Linguistic Sciences. 13:2.

- Barbara A. Holdrege (2012). Veda and Torah: Transcending the Textuality of Scripture. State University of New York Press. ISBN 978-1-4384-0695-4.

- Michael C. Howard (2012). Transnationalism in Ancient and Medieval Societies: The Role of Cross-Border Trade and Travel. McFarland. ISBN 978-0-7864-9033-2.

- Dhanesh Jain; George Cardona (2007). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-79711-9.

- Jamison, Stephanie (2008). Roger D. Woodard (บ.ก.). The Ancient Languages of Asia and the Americas. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-68494-1.

- Stephanie W. Jamison; Joel P. Brereton (2014). The Rigveda: 3-Volume Set, Volume I. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-972078-1.

- A. Berriedale Keith (1993). A history of Sanskrit literature. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-1100-3.

- Damien Keown; Charles S. Prebish (2013). Encyclopedia of Buddhism. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-136-98595-9.

- Anne Kessler-Persaud (2009). Knut A. Jacobsen; และคณะ (บ.ก.). Brill's Encyclopedia of Hinduism: Sacred texts, ritual traditions, arts, concepts. Brill Academic. ISBN 978-90-04-17893-9.

- Jared Klein; Brian Joseph; Matthias Fritz (2017). Handbook of Comparative and Historical Indo-European Linguistics: An International Handbook. Walter De Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-026128-8.

- Dalai Lama (1979). "Sanskrit in Tibetan Literature". The Tibet Journal. 4 (2): 3–5. JSTOR 43299940.

- Winfred Philipp Lehmann (1996). Theoretical Bases of Indo-European Linguistics. Psychology Press. ISBN 978-0-415-13850-5.

- Donald S. Lopez Jr. (1995). "Authority and Orality in the Mahāyāna" (PDF). Numen. Brill Academic. 42 (1): 21–47. doi:10.1163/1568527952598800. hdl:2027.42/43799. JSTOR 3270278.

- Mahadevan, Iravatham (2003). Early Tamil Epigraphy from the Earliest Times to the Sixth Century A.D. Harvard University Press. ISBN 978-0-674-01227-1.

- Malhotra, Rajiv (2016). The Battle for Sanskrit: Is Sanskrit Political or Sacred, Oppressive or Liberating, Dead or Alive?. Harper Collins. ISBN 978-9351775386.

- J. P. Mallory; Douglas Q. Adams (1997). Encyclopedia of Indo-European Culture. Taylor & Francis. ISBN 978-1-884964-98-5.

- Mallory, J. P. (1992). "In Search of the Indo-Europeans / Language, Archaeology and Myth". Praehistorische Zeitschrift. Walter de Gruyter GmbH. 67 (1). doi:10.1515/pz-1992-0118. ISSN 1613-0804. S2CID 197841755.

- Colin P. Masica (1993). The Indo-Aryan Languages. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-29944-2.

- Michael Meier-Brügger (2003). Indo-European Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-017433-5.

- Michael Meier-Brügger (2013). Indo-European Linguistics. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-089514-8.

- Matilal, Bimal (2015). The word and the world : India's contribution to the study of language. New Delhi, India Oxford: Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-565512-4. OCLC 59319758.

- Maurer, Walter (2001). The Sanskrit language: an introductory grammar and reader. Surrey, England: Curzon. ISBN 978-0-7007-1382-0.

- J. P. Mallory; D. Q. Adams (2006). The Oxford Introduction to Proto-Indo-European and the Proto-Indo-European World. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-928791-8.

- V. RAGHAVAN (1965). "Sanskrit". Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. 8 (2): 110–115. JSTOR 23329146.

- MacDonell, Arthur (2004). A History Of Sanskrit Literature. Kessinger Publishing. ISBN 978-1-4179-0619-2.

- Sir Monier Monier-Williams (2005). A Sanskrit-English Dictionary: Etymologically and Philologically Arranged with Special Reference to Cognate Indo-European Languages. Motilal Banarsidass. ISBN 978-81-208-3105-6.

- Tim Murray (2007). Milestones in Archaeology: A Chronological Encyclopedia. ABC-CLIO. ISBN 978-1-57607-186-1.

- Ramesh Chandra Majumdar (1974). Study of Sanskrit in South-East Asia. Sanskrit College.

- Nedi︠a︡lkov, V. P. (2007). Reciprocal constructions. Amsterdam Philadelphia: J. Benjamins Pub. Co. ISBN 978-90-272-2983-0.

- Oberlies, Thomas (2003). A Grammar of Epic Sanskrit. Berlin New York: Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-014448-2.

- Petersen, Walter (1912). "Vedic, Sanskrit, and Prakrit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. American Oriental Society. 32 (4): 414–428. doi:10.2307/3087594. ISSN 0003-0279. JSTOR 3087594.

- Sheldon Pollock (2009). The Language of the Gods in the World of Men: Sanskrit, Culture, and Power in Premodern India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-26003-0.

- Pollock, Sheldon (2001). "The Death of Sanskrit". Comparative Studies in Society and History. Cambridge University Press. 43 (2): 392–426. doi:10.1017/s001041750100353x. JSTOR 2696659. S2CID 35550166.

- V. RAGHAVAN (1968). "Sanskrit: Flow of Studies". Indian Literature. Sahitya Akademi. 11 (4): 82–87. JSTOR 24157111.

- Colin Renfrew (1990). Archaeology and Language: The Puzzle of Indo-European Origins. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-38675-3.

- Louis Renou; Jagbans Kishore Balbir (2004). A history of Sanskrit language. Ajanta. ISBN 978-8-1202-05291.

- A. M. Ruppel (2017). The Cambridge Introduction to Sanskrit. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-1-107-08828-3.

- Salomon, Richard (1998). Indian Epigraphy: A Guide to the Study of Inscriptions in Sanskrit, Prakrit, and the other Indo-Aryan Languages. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-535666-3.

- Salomon, Richard (1995). "On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

- Salomon, Richard (1995). "On the Origin of the Early Indian Scripts". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 115 (2): 271–279. doi:10.2307/604670. JSTOR 604670.

- Malati J. Shendge (1997). The Language of the Harappans: From Akkadian to Sanskrit. Abhinav Publications. ISBN 978-81-7017-325-0.

- Seth, Sanjay (2007). Subject lessons: the Western education of colonial India. Durham, NC: Duke University Press. ISBN 978-0-8223-4105-5.

- Staal, Frits (1986), The Fidelity of Oral Tradition and the Origins of Science, Mededelingen der Koninklijke Nederlandse Akademie von Wetenschappen, Amsterdam: North Holland Publishing Company

- Staal, J. F. (1963). "Sanskrit and Sanskritization". The Journal of Asian Studies. Cambridge University Press. 22 (3): 261–275. doi:10.2307/2050186. JSTOR 2050186.

- Angus Stevenson; Maurice Waite (2011). Concise Oxford English Dictionary. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-960110-3.

- Southworth, Franklin (2004). Linguistic Archaeology of South Asia. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-134-31777-6.

- Philipp Strazny (2013). Encyclopedia of Linguistics. Routledge. ISBN 978-1-135-45522-4.

- Paul Thieme (1958). "The Indo-European Language". Scientific American. 199 (4): 63–78. Bibcode:1958SciAm.199d..63T. doi:10.1038/scientificamerican1058-63. JSTOR 24944793.

- Peter van der Veer (2008). "Does Sanskrit Knowledge Exist?". Journal of Indian Philosophy. Springer. 36 (5/6): 633–641. doi:10.1007/s10781-008-9038-8. JSTOR 23497502. S2CID 170594265.

- Umāsvāti, Umaswami (1994). That Which Is. แปลโดย Nathmal Tatia. Rowman & Littlefield. ISBN 978-0-06-068985-8.

- Wayman, Alex (1965). "The Buddhism and the Sanskrit of Buddhist Hybrid Sanskrit". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 85 (1): 111–115. doi:10.2307/597713. JSTOR 597713.

- Annette Wilke; Oliver Moebus (2011). Sound and Communication: An Aesthetic Cultural History of Sanskrit Hinduism. Walter de Gruyter. ISBN 978-3-11-024003-0.

- Whitney, W.D. (1885). "The Roots of the Sanskrit Language". Transactions of the American Philological Association. JSTOR. 16: 5–29. doi:10.2307/2935779. ISSN 0271-4442. JSTOR 2935779.

- Witzel, M. (1997). Inside the texts, beyond the texts: New approaches to the study of the Vedas (PDF). Cambridge, Massachusetts: Harvard University Press.

- Iyengar, V. Gopala (1965). A Concise History of Classical Sanskrit Literature. Rs. 4.

- Parpola, Asko (1994). Deciphering the Indus Script. Great Britain: Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-43079-8.

แหล่งข้อมูลอื่น

แก้- "INDICORPUS-31". 31 Sanskrit and Dravidian dictionaries for Lingvo.

- Karen Thomson; Jonathan Slocum. "Ancient Sanskrit Online". free online lessons from the "Linguistics Research Center". University of Texas at Austin.

- "Samskrita Bharati". an organisation promoting the usage of Sanskrit

- "Sanskrit Documents". — Documents in ITX format of Upanishads, Stotras etc.

- "Sanskrit texts". Sacred Text Archive.

- "Sanskrit Manuscripts". Cambridge Digital Library.

- "Lexilogos Devanagari Sanskrit Keyboard". for typing Sanskrit in the Devanagari script.

- "Keyswap – IAST Diacritics Windows Software". YesVedanta. 9 August 2018. — Keyboard Software for typing in the International Alphabet for Sanskrit

- "Online Sanskrit Dictionary". — sources results from Monier Williams etc.

- "The Sanskrit Grammarian". — dynamic online declension and conjugation tool

- "Online Sanskrit Dictionary". — Sanskrit hypertext dictionary